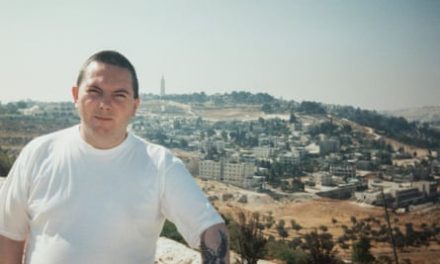

Kirkland Johnson, a Jamaican expatriate, is still grappling with the Windrush trauma triggered by repeated travel problems and the loss of his teaching career in the UK

The 68-year-old, who left the village of Lluidas Vale, St Catherine, for England when he was about nine, is disputing a proposed £40,000 payout under the Windrush compensation scheme and deems it an insult.

Johnson’s status came under scrutiny from the Home Office in about 2015 and he claims that he was prevented from working.

Having held a Jamaican passport for six decades, Johnson believed the right-to-remain inscription in the document insulated him from immigration and work problems.

But he said his faith in the British state was shaken when he was informed by a government official that he would no longer be able to teach.

Jolted by the news, the stability of his family life was threatened and their financial future undermined.

“Initially, I thought this guy was having a joke with me. Then the reality kicked in after some time. I can’t even explain the feeling because I had worked so hard to become a teacher and here I was teaching for the past 14-15 years and they’re telling me that I didn’t have a right to work,” Johnson, who taught maths at Weston Favell academy in Northampton, told the Guardian.

“We had insurance policies that had to be sold. Whatever we had, we had to sell it to make ends meet. The constant worry – my children were concerned that the police would come and take me away. They were in tears; my wife was in tears.”

Experiences such as Johnson’s have fired the activism of Bishop Dr Desmond Jaddoo, the chair of the Windrush National Organisation. He has called for deeper reforms of Britain’s immigration policy and a moratorium on deportations until all Windrush concerns have been resolved.

Jaddoo argues that British society has for too long “put a small plaster over a massive crack”.

“The fact that people ask me where I’m from shows clearly that there is a non-acceptance, that if your face is not white, you are not considered to be British … When people were saying, ‘I have been here 50 years, I came here as a child’, they basically said they were liars, they were told, ‘You’ve got no right to be here.”

That Windrush immigrants have been forced to go through hoops to meet the bar of eligibility is an indictment on Britain’s rhetoric of multiculturalism and raises serious questions about British identity, the lobbyist says.

“We know about the issue of no blacks, no Irish, no dogs. We know about people being turned away from churches … and also being called immigrants when my mother, my father and many others were born British, and they were told they were British, and when they arrived in the UK they arrived with a British passport,” Jaddoo said.

Prof Martin Levermore, an independent adviser to the Windrush compensation scheme, bemoaned that families legitimately invited to rebuild war-ravaged Europe and who contributed to its development “became an invisible group because organs of government forgot they existed”.

As of April, £61.26mwas paid out in response to 1,637 claims, with more than £11m more offered in restitution.

Eighty-nine residents in Jamaica have received status and compensation under the scheme while 351 have been granted temporary indefinite leave to remain.

Data from the Windrush compensation scheme also show that 2,653 Jamaicans have had British citizenship conveyed, while 357 others have been granted indefinite leave-to-remain status. The defined period for compensation and status redress stretches from 1948 to 1986.

Levermore, who was appointed in March 2021, said there had been progress in expediting the processing of applications and cited improvement in eligibility criteria, including homelessness.

However, he says the compensation scheme should not be conflated with the intensifying lobby for Caribbean slavery reparations.

Estimates by a group of American economists this month put Britain’s slavery reparations bill for 14 countries at $24tn (£18.8tn), with Jamaica a proposed beneficiary of $9.5tn.

Levermore said: “[By including] broader wrongs of not just the UK but any colonial power, you … confuse the issue, and I think the element is looking not at centuries gone by but years gone by of incorrect application of immigration rules, which have significantly created today’s trauma for individuals. I think you have got to keep them separate.”

For some Caribbean migrants, the Windrush scandal has resurrected memories of racial discrimination in the UK. Meanwhile, others say they experienced no, or negligible, prejudice.

after newsletter promotion

Gloria Wilson, who emigrated from St Ann, Jamaica, in 1961 to follow her childhood sweetheart and eventual husband Lloyd, said she did not face racism when she arrived in Hertfordshire to find only a smattering of black people.

“When it comes to discrimination, I never saw it. I just never saw it … If they said anything behind my back, I never heard,” she said.

Gloria, 82, initially worked at a pharmacy and later a nursing home before retirement, while Lloyd was an auto engineer producing parts for Ford Motor Company in Letchworth for his entire career.

The couple, who assumed British citizenship, returned to live in Jamaica in 2003 after four decades in the UK.

Percival LaTouche, who has been the face of Jamaica’s resettlement movement for decades, said he had only one direct brush with discrimination in his 26 years spent in England. He proudly recounts imposing his 6ft frame on a man who called him a “black bastard”, finishing him off with a right hook.

Migration from the Caribbean after the second world war not only helped the reconstruction of Britain but continues to bring foreign exchange inflows to the Jamaican economy.

Central bank data put remittances for 2022 at $3.44bn, a slight decline from the record high of $3.497bn a year earlier. Those billions of dollars are important on a micro level, keeping many households afloat. A Bank of Jamaica survey from more than a decade ago showed that 85% of remittances covered utility expenses and consumables, providing a snapshot of the multiplier effect of migration on Caribbean economies.

A 2017 study by the Caribbean Policy Research Institute thinktank revealed that the diaspora’s total contribution through remittances, investment, philanthropy, exports and tourism represented 28% of Jamaica’s national output.

But migration has also taken a toll on the island that transcends dollars and cents. Besides the brain drain that has eroded its intellectual and technical capacity, there have been psychosocial and emotional consequences for many families.

Dr Claudette Crawford-Brown, a retired senior lecturer at the University of the West Indies and director of the Institute for Caribbean Children and Families, coined the term “barrel children” nearly four decades ago to capture the fragmentation that characterised broken homes across the Atlantic divide.

Barrel children are those who have had no or negligible emotional nurturance after their parents migrated. Crawford-Brown says the phenomenon intensified in the post-Windrush era with matrifocal support systems collapsing as more women seized the opportunity to work in the US and Canada when labour migration shifted from the UK.

“The issue of migration changed significantly after the doors of migration closed to the colonised countries in Britain. The doors of England closed and there was a movement towards the USA and Canada. In the 1970s, the labour movement changed and the women started leaving,” the academic said.

“The point I have made over and over is that when the mothers leave – informal commercial importers, higglers, nurses – it causes a fundamental shift of earthquake proportions in our family structure. Why? When men leave … a family in the Caribbean, it has a different impact than when women leave.”

That has had consequences along socioeconomic and class lines, with poorer Jamaicans likelier to have more fragmented migration. According to Crawford-Brown, middle-class families tend to migrate together while working-class families were more prone to migrate incrementally – or one by one.

Crawford-Brown also believes the evolution of “drug-courier mums” – driven by an entrepreneurial, utilitarian philosophy – has worsened family dysfunction compared with the Windrush era.

“We have to find those mothers and children. Our guidance counsellors, social workers, therapists have to find those children who are not getting the care they need and who lack emotional nurturance. We have to find those barrel children and make sure they receive support from the community, government, wherever, so that they do not end up antisocial and criminals and messed up psychologically and emotionally and have mental health problems,” she said.

Crawford-Brown’s late son, Omar W Brown Jr, a sociologist at Boston University, warned in a soon-to-be-published book, Beyond the Barrel, that modern migration had “fundamentally” changed the sociology of the Caribbean and that children had become collateral damage.

“He felt strongly that without the necessary support to monitor these families, we are in danger of having a fallout from the migration experience … He is suggesting that society, as a whole, could lose out if we are not careful.”

Design by the Guardian editorial design team: Chris Clarke, Ellen Wishart, Harry Fischer, Alessia Amitrano

Join the exciting world of cryptocurrency trading with ByBit! As a new trader, you can benefit from a $10 bonus and up to $1,000 in rewards when you register using our referral link. With ByBit’s user-friendly platform and advanced trading tools, you can take advantage of cryptocurrency volatility and potentially make significant profits. Don’t miss this opportunity – sign up now and start trading!

Recent Comments